Fire and water

June 25, 2011

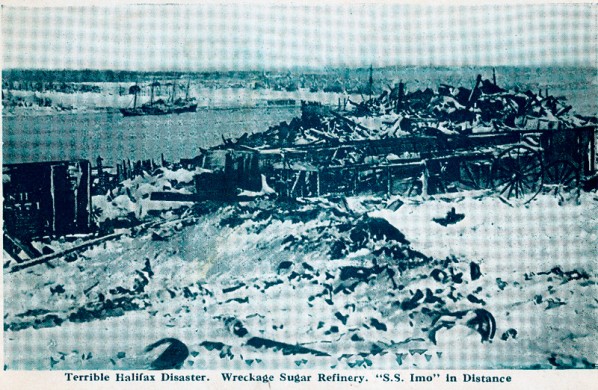

A fireball 1.6 km high. A tsunami and a blazing inferno. Sixteen hundred buildings destroyed and twelve thousand damaged. Shattered windows in a village situated a full 100 km from the explosion. Thousands of dead and wounded. Images of Japan or Indonesia come to mind…and yet, this drama unfolded right here at home. Revisit the tale of an unprecedented catastrophe and recall the courage of those who braved impossible odds to save the lives of others…and lost their own in the attempt.

December 6th, 1917: a typical morning in the busy port of Halifax. There is plenty of hustle and bustle here at the peak of the First World War with the constant coming and going of ships between America and Europe. But at 8:43 am everything goes topsy-turvey. Two ships collide. In a desperate effort to avert disaster, a man assembles a small but courageous crew and sets out to confront multiple dangers: fire, explosion, devastation. Today, the Canadian War Museum honours their memory.

Sailing towards their doom

Ships loaded with munitions are nothing new to the port of Halifax – in 1917 war is a-raging. On the fateful Thursday morning of December 6th, the Norwegian relief vessel Imo leaves the port via the left channel, while at the same moment, the French munitions vessel Mont-Blanc takes the very same route…in the opposite direction! Bad maneuvers and stubbornness make for a dangerous mix – neither captain wants to yield the way and disaster strikes: the ships collide.

Very quickly, benzene stored on the deck of the Mont-Blanc is spilled and ignites. The crew abandons ship and makes for the Dartmouth shore – while the flames take hold of the cargo: over 2 400 tons of high explosives.

In a desperate attempt to tow the Mont-Blanc away from the harbour, the captain of the HMCS Niobe of the Royal Canadian Navy sends a pinnace to tow the ship out to sea. Commanding the small crew of volunteers is Acting Boatswain Albert Charles Mattison, aged 44. The sailors try to board the ship in order to attach a hawser that would enable the towing maneuver – but to no avail. At precisely 09:04:35, the Mont-Blanc is blown to bits in history’s largest man-made explosion before the testing of the atomic bomb. The force of the explosion leveled everything in its path: the harbour, the city, and, of course, the pinnace and its crew.

Posthumous medal

On February 18, 1919, King George V posthumously awarded Albert Charles Mattison the Albert Medal for Lifesaving at Sea. This decoration was first instituted in 1866 and named in honour of Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the Prince Consort and husband of Queen Victoria. The medal was awarded posthumously to individuals for saving lives at sea until 1949. By 1971, all surviving recipients of the Albert Medal were invited to exchange it for the George Cross.

The Canadian War Museum has recently acquired the medal that was awarded to Mattison. Made of bronze and enamel, it was purchased for the sum of 19 000 £ (about 30 000 $). This new addition to the Museum’s collection commemorates the sacrifice and courage of Albert Chales Mattison and to all the others who, like him, lost their lives in the Halifax Harbour explosion – an event considered to be one of the most terrible tragedies in Canadian history.