Relics in the Shadows

October 22, 2021In December 2021, the Canadian Museum of History will open an exhibition, Lost Liberties − The War Measures Act, generously supported by a grant from the Endowment Council of the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund. The exhibition explores three periods in Canadian history when personal freedoms were curtailed. In this article, Professor Lubomyr Luciuk shares his thoughts on the importance of artifacts in presenting stories about Canada’s first national internment operations of 1914−1920.

CMH IMG2017-0043-0045-Dm

For me, two artifacts and a photograph best evoke the experiences of those who suffered through Canada’s first national internment operations. One is a small cross, hand-shaped out of the barbed wire that once encircled the camp near Morrissey, British Columbia, where “enemy aliens” were held. Recovered from beneath the remnants of that enclosure only a few years ago, the cross remains a mystery: we will never know who crafted it or left it buried there. Clearly, however, he was a person of faith, whose Christian belief provided hope. This cross is on permanent display in the Canadian History Hall.

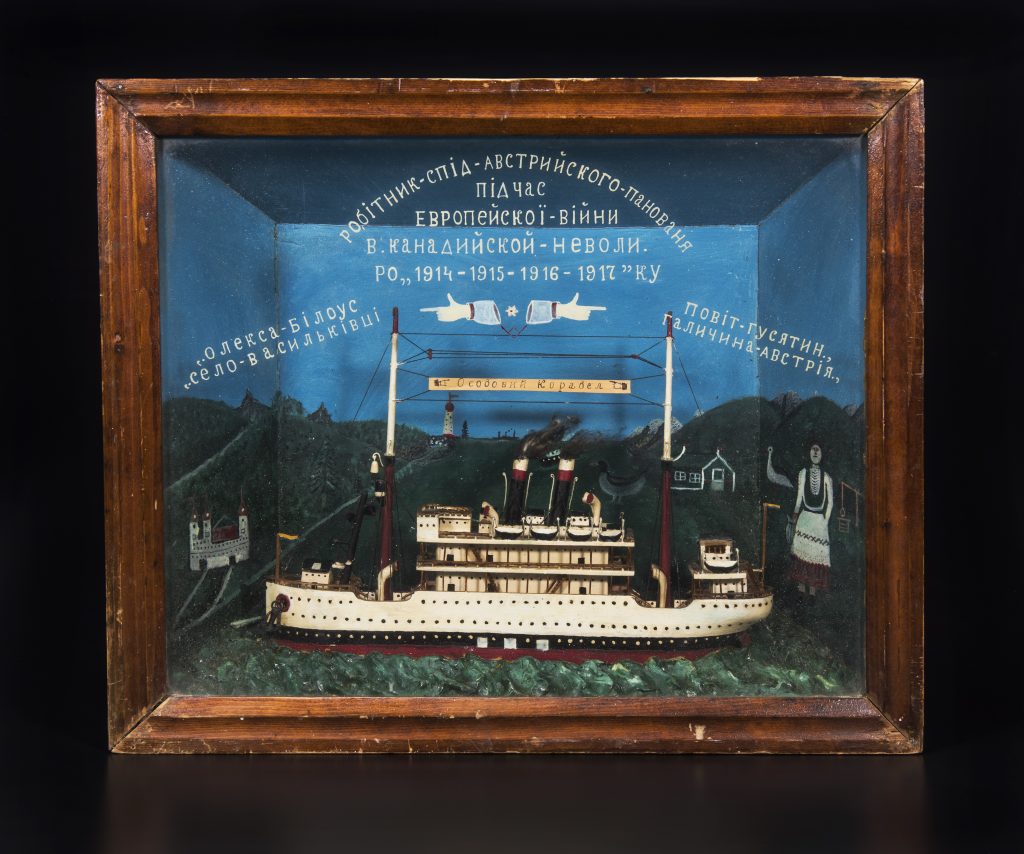

The second is a shadowbox made by Oleksa Bilowus, a Ukrainian who carefully captioned it so that anyone looking at it would know his story. He left a homeland under Austrian rule and immigrated to Canada, only to find himself imprisoned from 1914 to 1917.

Shadow Box – Oleksa Bilowus – CMH IMG2018-0175-0002-Dm

Who was he? Where was he held? Who did he leave behind? Is the woman his mother, his wife, a lover? We do not know. He may have been held at Spirit Lake in Quebec, or perhaps in western Canada. The imagery suggests that, while imprisoned, he was shifted from one camp to another — a not-uncommon fate.

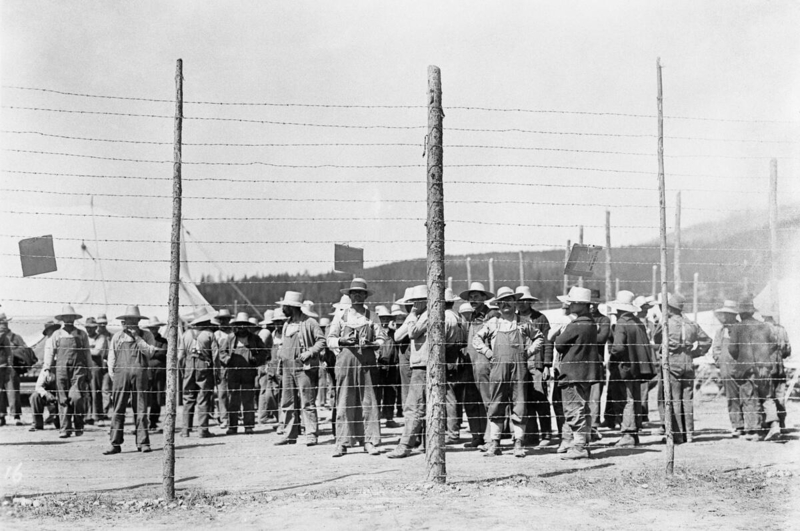

And, finally, there is a photograph that captures a moment in time, depicting dozens of internees at the Castle Mountain Camp in Banff. Forced to do heavy labour for the profit of their jailers, these men literally helped build the infrastructure of many of Canada’s most famous national parks.

Internees at the internment camp, Castle Mountain, Alberta – Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources – Digital Collections, University of Calgary (CU186787)

The image reveals the conflicted feelings of the internees. Some appear indifferent, but one man covers his face, as though not wanting to be identified or known. But there is another internee who stares at the photographer defiantly, arms firmly on hips. He wants you to know that he will resist any attempt to erase his experience — and those of many others — from Canada’s historical narrative. Like everyone else branded an “enemy alien” and transported to this country’s frontier wildernesses, this man had done no wrong.

The people who made these objects, and who are depicted in the photograph, were interned because of who they were, and where they had come from. Each, in their own way, struggled to leave traces of their experiences, left relics for us to ponder and pray over — guideposts to what they lost when their liberties were unjustly taken away.

Lubomyr Luciuk is a Canadian academic and author of books and articles in the field of political geography, and Ukrainian and Ukrainian Canadian history. He is currently a full professor at the Royal Military College of Canada.