Hundreds of thousands of people visit the Canadian War Museum every year. Their experience is shaped — even before they open the front doors — by the distinctive design of the building.

Commemorating and interpreting the history of war is a challenging and meaningful mission. Armed conflict involves the full spectrum of human experience, from violence and cruelty to heroism and hope.

The podcast episode “Concrete and Light” offers an intimate look at the Canadian War Museum. Listeners learn how the building was designed to challenge the conscience and serve as a source of healing and regeneration. In the episode, we hear from the building’s designers, curators who develop exhibitions, and staff who work with visitors every day.

You can read some of what they have to say below. Listen to the full episode for more.

Architecture, history, and hope

Emmanuelle van Rutten was a junior architect on the team that designed the building, under the leadership of the late Raymond Moriyama. Reflecting on what it’s like entering the Museum, she says, “I find it quiet when you come into the Lobby and there’s a moment of serenity but also sort of discomfort.”

This tension is true of the exterior as well. The Museum was the first building constructed on an area of long-abandoned, grassy, industrial land. The idea that growth and renewal remain possible after destruction and loss was important to the design of the building.

Aerial view of the location of the Canadian War Museum on LeBreton Flats in Ottawa.

Corporation/PCL Constructors

Van Rutten says: “One of the things that actually inspired us was the grass that was growing on the field. It seemed to fit with a lot of the themes that we were exploring about nature, healing.” And so, from the west and north, the building rises organically out of the soil. Its sloped living roof offers a sense of continuity and connection. But to the east, large glass windows and a soaring concrete and metal fin give the Museum a dramatic street presence.

Many aspects of the building draw on the materials and the look of wartime structures. “You’ve got ramps going up to the exhibit space and the walls are inclined towards you,” van Rutten notes. “And this is there to really kind of create this sense that you’re inspired by bunkers, but you’re in a very utilitarian and strong building.”

Bunker-like, slanted concrete defines Commissionaires Way, which connects the LeBreton Gallery with the Lobby.

Canadian War Museum

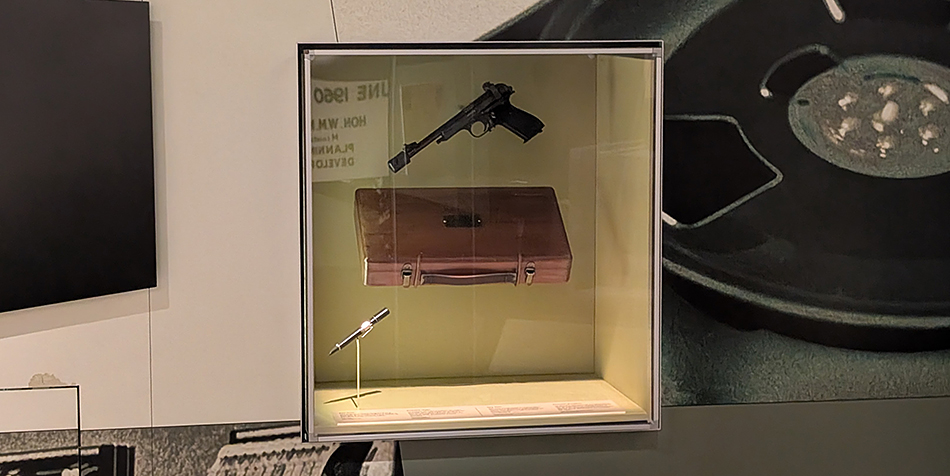

Telling meaningful stories

It’s a complicated building, and the exhibitions within tell complicated stories. The experience of war is deeply human in its tragedy and heroism. “We’re not just telling dry history here: the number of people who went to this battle,” says historian Danielle Teillet. “We’re trying to share personal stories of individuals, and we’re trying to share things that people can connect with.”

Teillet has both professional expertise and a personal connection with the history of war. Her grandfather served in the Second World War, and she discovered documents about aspects of his experience that he had never talked about.

She reflects on this when working on exhibitions. “You want to share some of these stories, recognizing that these are real people,” she says. “They’re not numbers, they’re not statistics. Each individual person had a family and a story and friends and parents and their own experiences.”

Personal encounters

Visitors arrive in the building for many reasons. Staff members who work with visitors often give directions and answer questions. They also sometimes offer a sympathetic ear for heartfelt stories of connection, survival or loss.

There is a damaged UN peacekeeping Jeep displayed in the “From the Cold War to the Present” gallery. Program interpreter Jacques Giasson was working nearby when a visitor asked him to see it. It became clear that this man was having a strong reaction to seeing the vehicle. Giasson recalls: “I went up to him. I say, ‘Sir, obviously this Jeep has a big impact on you.’ He said, ‘For a good reason. I was driving this vehicle when it got attacked.’”

The main galleries contain many meaningful objects, including this UN Jeep damaged during the Yugoslavian War.

Canadian War Museum

Giasson reflects: “That’s one of the things that you know. Sometimes you’re going to have people who have a direct link with the artifacts that we have in the Museum.”

Another program interpreter, Rob Gauvin, also had a meaningful encounter with a visitor who was at the Museum processing a tragic loss. He met a woman standing near a vehicle used by Canadian troops in Afghanistan. She revealed that her son had been killed serving there. “I don’t think I could ever say anything to console her,” Gauvin recalls. “She just had a moment. And I just happened to be here and she was here. It was an extremely powerful moment. It’s a moment I never forgot.”

Compassion and hope

The different spaces in the building allow for a full range of experiences and emotions related to war. Visitors can encounter stories of violence, but also moments of reflection. Program interpreter Camille Brouzes says, “One of the most, I would say, healing spaces is Regeneration Hall. It’s a beautiful space because it has that little whistling sound.”

Moriyama Regeneration Hall features a soaring ceiling and a quiet soundtrack of whistling wind.

Canadian War Museum

This large room is filled with the soft sound of wind, recorded in the unfinished building while it was under construction. The sound reminded architect Raymond Moriyama of his childhood treehouse. It was a place of comfort and solace at the internment camp he was sent to with his family during the Second World War. It was also the first thing he ever built.

“I’ve done guided tours with people in the military,” Brouzes recalls. “They say that that sound is relieving because it sounds like a white noise.” Spaces like Moriyama Regeneration Hall and Memorial Hall support visitors seeking a place for solemn remembrance or quiet reflection.

Gauvin reflects on the human connection involved in remembering and understanding conflict. He says, “As someone who’s always loved history, tragedy happens in war and there’s a form of compassion that can come from out of that.”

“Raymond was clear this was not about glorifying war,” says van Rutten. “And I think it was clear to him that regardless of presenting how difficult war is, there’s also the question of hope and regeneration.”

Hear more about all these stories in “Concrete and Light: Inside the Canadian War Museum”:

The Museum’s large windows and large fin face east, towards downtown Ottawa and Parliament Hill.

Canadian War Museum

Steve McCullough

Dr. Steve McCullough is the Digital Content Strategist at the Canadian Museum of History and the Canadian War Museum. His work in digital storytelling involves compassionate and evidence-based efforts to address history, meaning and identity in our fragmented and polarizing, but also vibrant and interconnected, online environment.